Test Preparation Realities

Many people have erroneously been led to believe: test preparation is nothing more than having someone answer a few questions, or that preparation teaches you a few tricks to identify answers. This is a complete fallacy! Educators who prepare students for college / graduate school entrance exams must be excellent at investigating a student’s academic knowledge yet be talented to develop curriculum that will address a student’s deficiencies.

Before starting your preparation you must be completely honest with yourself concerning your: academic knowledge, ability to apply this knowledge, study routine effectiveness, dedication to remain academically and task focused, and willingness to accept you may never improve your score. You are where you are because the decisions you have made. If you did not completely understand your academic course fundamentals, then you must master that information.

You are an academic product of your decisions! If you have not been academically focused and disciplined your college / graduate school entrance exam scores will reveal it!

Test Preparation commitment varies depending the exam (ACT® / SAT®, GRE®, or MCAT®) you are preparing for. For the majority taking the ACT® / SAT® you should plan on spending a “minimum” of 15 weeks studying.

The GRE® is a much more challenging exam and you should plan on spending at least a semester studying, if not longer.

The MCAT® is a complex exam and you will spend 7 hours and 30 minutes, including breaks, testing. You should plan on studying about a year for the exam.

High School Academic Timeline Importance

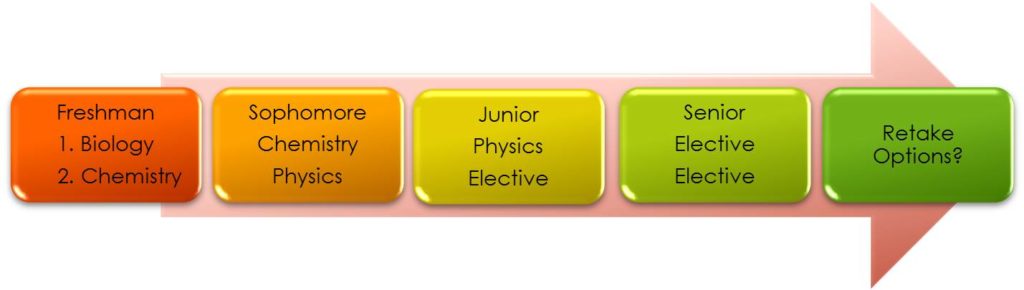

I cannot emphasize the importance of properly aligning one’s high school course work with college entrance exam prerequisites. It is vital that you complete the prerequisites prior to taking the exam(s). You should complete your high school course work in such fashion that you give yourself ample time to study for either, or both The ACT® and SAT®. The sooner you can complete entrance exam prerequisites the more leverage you will have over either exam. Pay specific attention to the different course orientations concerning the math and science timeline below.

Mathematics Timeline

Are you familiar with the phrase: “the early bird gets the worm?” Keep this in mind while planning your high school courses because the sooner you complete Algebra II the sooner you can begin preparing properly for the math exam of The ACT® and SAT®. If you can complete Pre-calculus by your sophomore year it will further prepare you for the math challenges. The conceptual aspects of the math exams require individuals to possess a mathematics maturity in which one recognizes mathematical relationships in order to solve abstract problems.

The illustration presents three math pathways demonstrating when the Algebra II course will be completed. It also illustrates when an individual will have enough math content to begin preparing for either the ACT® or SAT®. The first line illustrates when the majority of students will complete Algebra II. Completing Algebra II your junior year will limit your preparation time to roughly the summer of your senior year. Many students in this position want to target the September exam of their senior year, but fail to realize the mathematical challenges that lay ahead. If you set up your course math schedule to complete Algebra II your sophomore year you will give yourself a year to prepare, then your stress will be significantly reduced! Completing Algebra II, as depicted in the third line, during the freshman year will give you two plus years to prepare, then give you a chance to complete an advanced math course providing you more leverage over the math exam. It is vital to set up your math timeline properly and the best advice I can give you is to complete the Algebra II course your freshman year.

Science Timeline

Again, “The Early Bird Gets The Worm” holds true regarding the science timeline. Navigating high school curriculum and planning courses each year must be a planned priority based on future goals, and it is vitally important! The sooner you complete all your ACT® and SAT® prerequisite science courses the better prepared you will be to leverage those science fundamentals. Completing your Biology course during the 8th grade year will position you to complete chemistry and physics sooner. While reviewing the science timeline above pay attention to the course arrangement. A student who begins the freshman year with Chemistry then completes Physics as a sophomore will position them-self to begin preparing for the exams sooner, whereas completing Biology the freshman year limits preparation time.

The ACT® / SAT® evaluate a student’s ability to analyze scientific data and a strong understanding of science fundamentals is necessary. Students will need time to develop evaluation techniques to interpret the data based questions. The ACT® / SAT® design their science assessments differently from one another. The ACT® utilizes data from published journal papers to assess student’s science skills while the SAT®, for instance will present an advanced science essay – representing a lecture – then assess the student’s ability to grasp, and use that information to answer a series of specific application based questions.

Test Preparation Insight

Test preparation is complex, full of unexpected challenges requiring students and educators to be dedicated to fulfilling their respected roles. Educators should be academically fluent, multi-functional to act as both an academic coach and a content specialist! Students not only face academic deficiencies, but confidence issues which require educators to understand leadership and development principles to support and counsel students while navigating the process. To accomplish these monumental task’s educators must never be willing to settle for second best, and students must adopt this mentality.

An academic coach should be able to develop individualized strategic plans to navigate the exam format; develop a student’s psychology to remain confident; possess critical leadership and development skills to properly advise students relating to their academic development phases; and be able to teach students how to identify their personal and academic deficiencies. An academic coach should also be able to function as an experienced professional educator with the knowledge to: identify and correct academic deficiencies; create strategic academic plans; teach students methods to analyze scientific data; teach students how to become strong critical readers; teach students how to edit and write effectively; and teach students how to leverage mathematics conceptually!

The Importance of Data

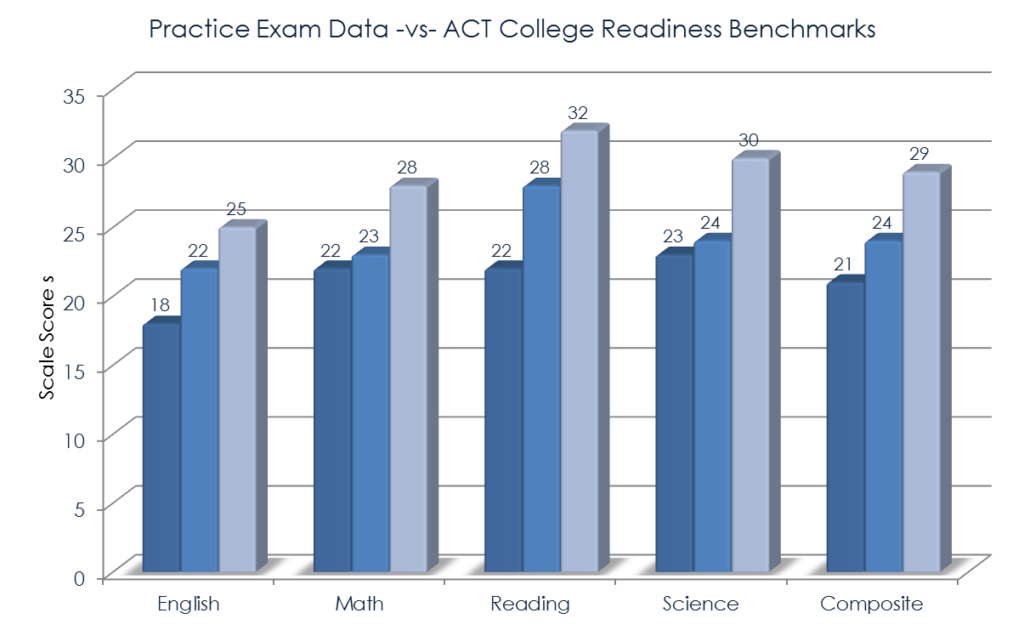

This graph is referencing a student’s ACT® baseline exam scale scores related to college readiness benchmarks, and the follow-up exam. The first bar graph within each category from left to right refers to college readiness benchmark scores. The middle bar graph refers to the student’s baseline scores. The last bar graph represents the follow-up exam results as the student’s deficiencies are being investigated and corrected. This is only one of many follow-up exams to come. These are not end-point results; they are results as a student transitions through 15 weeks of training.

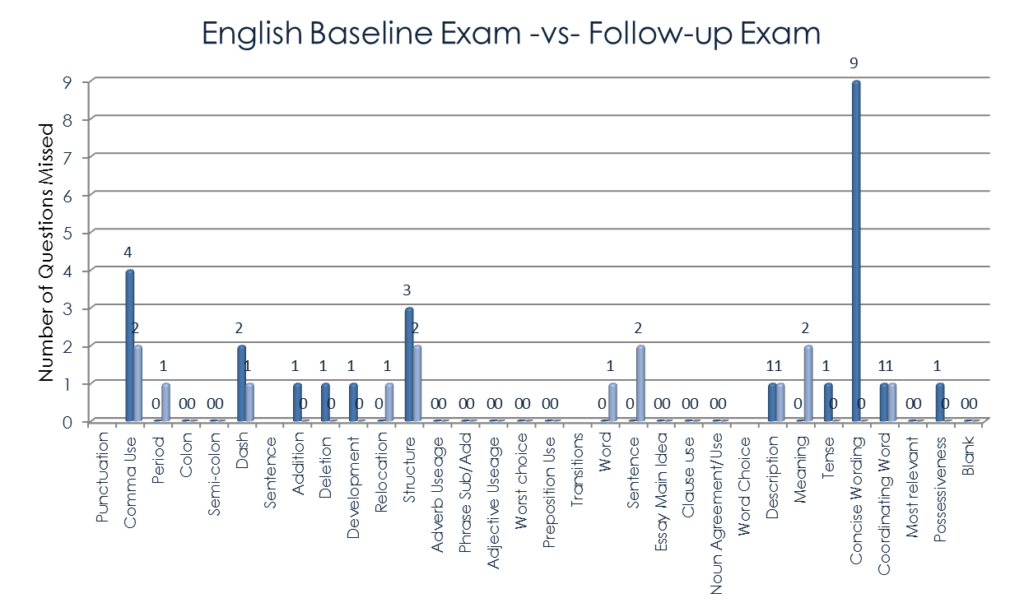

This ACT® English graph illustrates a student’s baseline results (dark blue bars) versus a follow-up exam (light blue bars) results. The light blue bar graph represents results as the student’s deficiencies are investigated and discussed. These are not end-point results; they are results as a student transitions through 15 weeks of training.

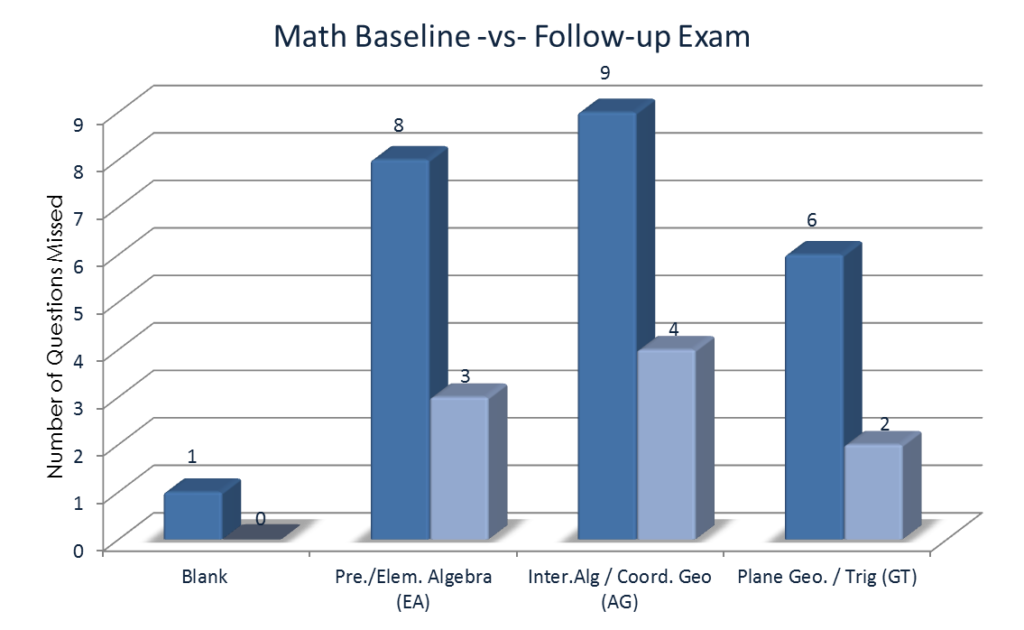

This math result graph illustrates a student’s baseline results (dark blue bars) versus a follow-up exam (light blue bars) results. The light blue bar graph represents results as the student’s deficiencies are investigated and discussed. These are not end-point results; they are results as a student transitions through 15 weeks of training.

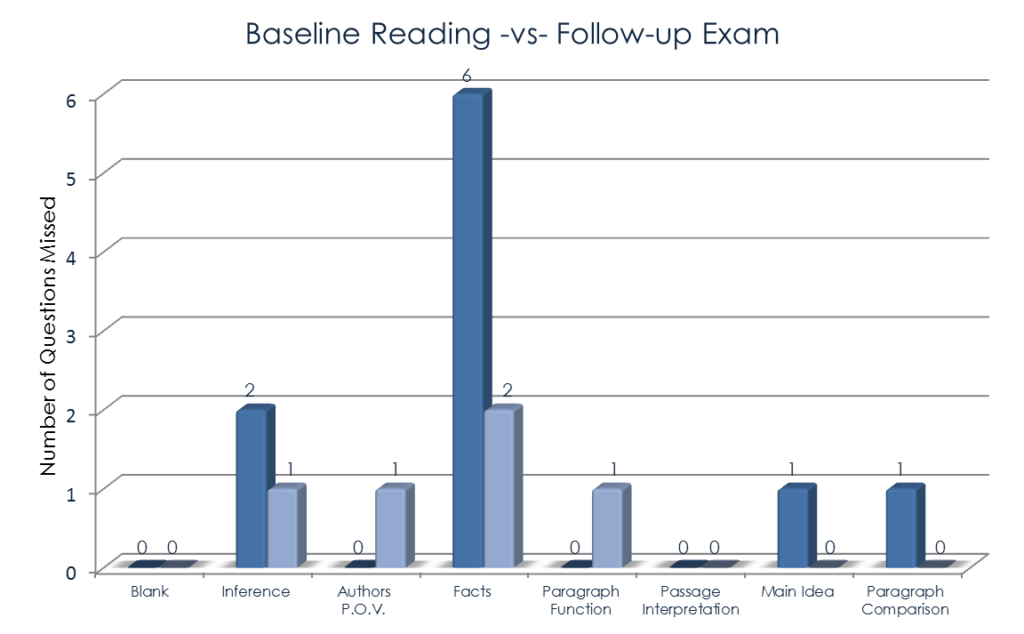

The reading result graph illustrates a student’s baseline results (dark blue bars) versus a follow-up exam (light blue bars) results. The light blue bar graph represents results as the student’s deficiencies are investigated and discussed. These are not end-point results; they are results as a student transitions through 15 weeks of training.

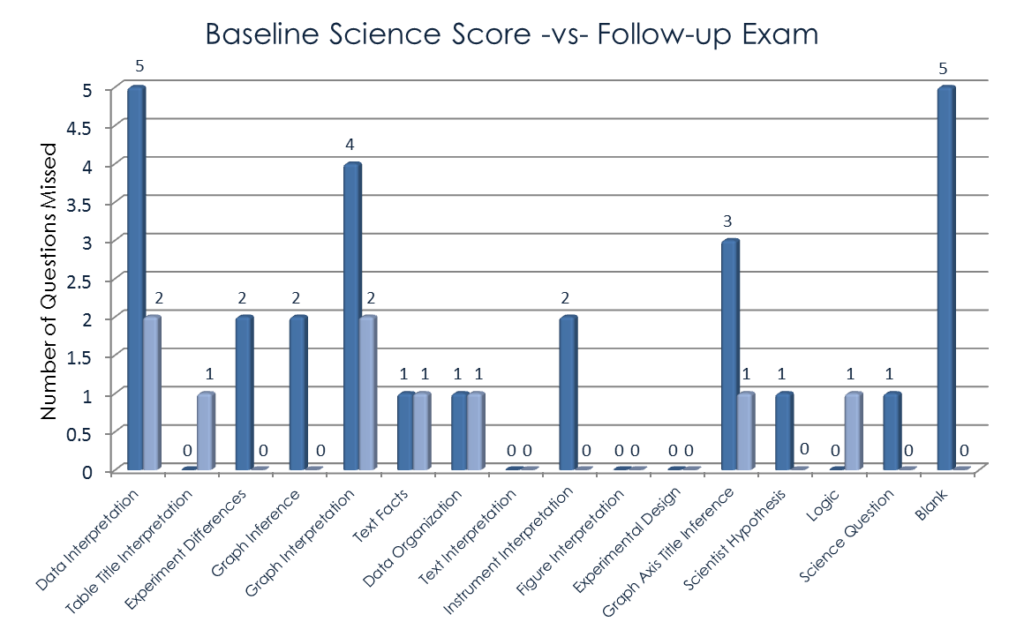

This science result graph illustrates a student’s baseline results (dark blue bars) versus a follow-up exam (light blue bars) results. The light blue bar graph represents results as the student’s deficiencies are investigated and discussed. These are not end-point results; they are results as a student transitions through 15 weeks of training.

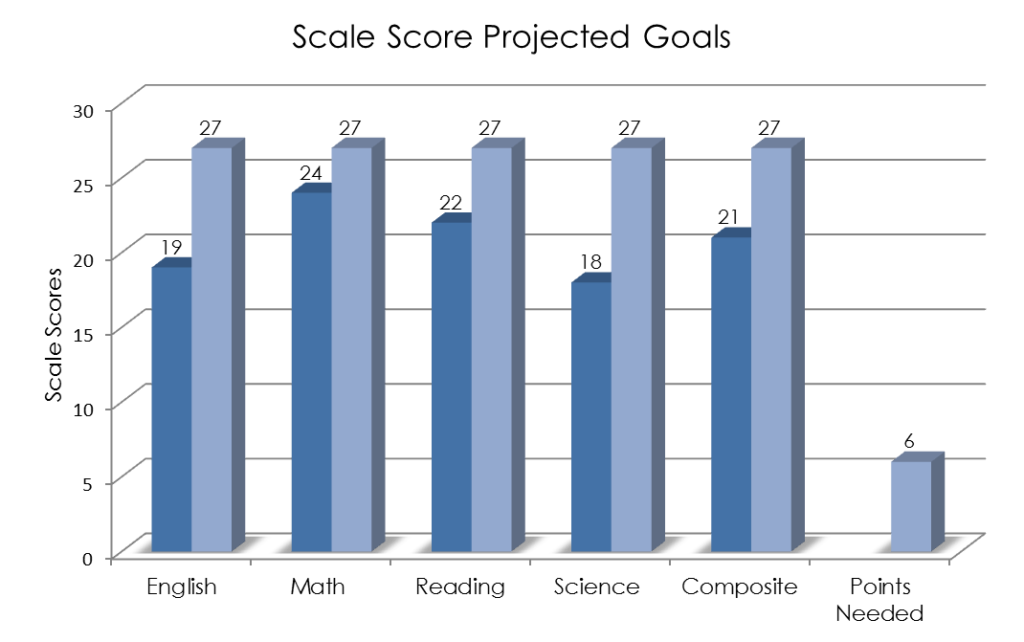

The dark blue bars refer to a student’s baseline scale scores. The light blue bars refer to a student’s scale score goals. Notice the scale score points needed. The additional scale score points needed to achieve a composite of 27 is 6. The actual raw number of questions needed to achieve a composite of 27 is addressed on the Raw Points Projection graph below. Please pay attention to how the actual number of questions relate to the scale score points.

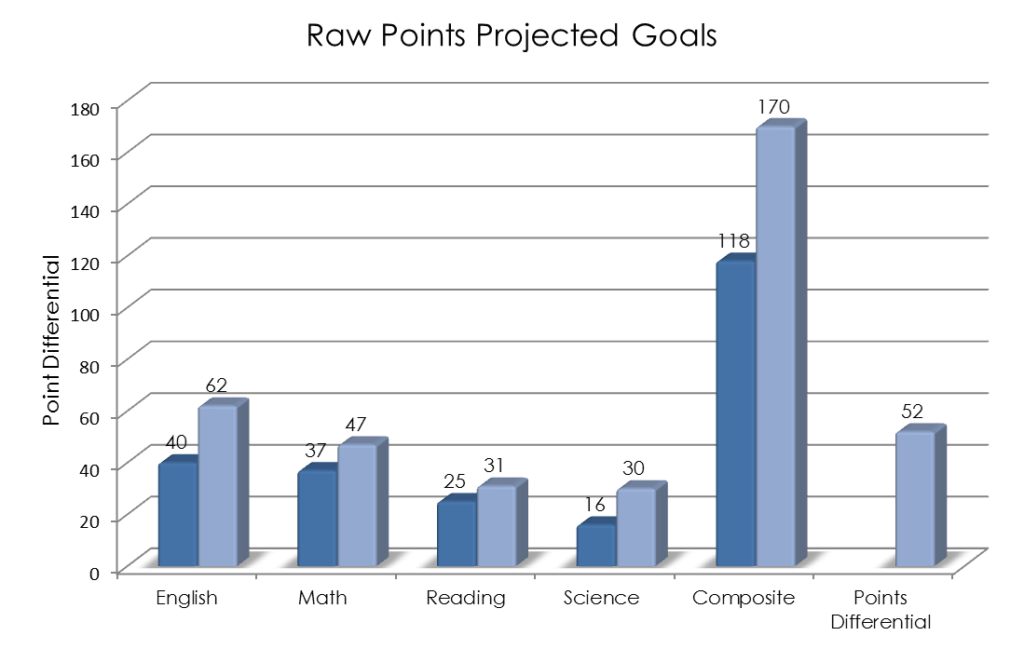

The Raw Points Projected Goal graph illustrates the number of questions a the student correctly answered to score a composite of 21 (dark blue bars), and the number of questions that one must answer to achieve a higher score related to their scale score projected goal of 27 (light blue bars). The point differential refers to the total number of additional questions one must correctly answer to advance their scale score from a 21 to a 27. These are not end-point results; they are results as a student transitions through 15 weeks of training.

Homework

Individuals that believe they must complete assignments for the sake of completing assignments will not perform well on college or graduate school entrance exams. Correcting one’s knowledge takes time, and it’s not an overnight process! If you want a perfect score it takes effort beyond what you are customary to. Many students believe studying is memorizing an exam topic list. This is not studying. A student must be able to conceptually apply knowledge. You must have the intent to master your academics and many people will need to change study approaches immediately! To achieve conceptual understanding you must be curious about the topics you are studying, then take an investigative approach to using that knowledge.

Are you tying to multitask while studying? If you are, then you must STOP! Multitasking can diminish cognitive performance and memory. To properly create memory pathways your complete attention must be focused on the subject you are trying to understand. When multitasking your attention is placed on distractions, it becomes more difficult to sustain your attention, and instead of developing focused attention you develop a scattered state of attention. The scattered state of attention prevents you brain from forming long term memory and reduces your ability to conceptually apply information constructively.

You will have homework on a daily basis, seven days a week. If you try to rush through it, complete it within a day, or within a couple of days you will never be exposed to the information long enough to create long term memory. Your assignments will be application based, specifically designed for you, and furthermore organized according to your progress. You will be tested contingent to your progress. You will typically face multiple English editing exercises, application based mathematics, various reading passages, followed by application based science analysis homework for a “minimum” of 15 weeks. You will have multiple resources and textbooks. Everything you do will be critically evaluated and scrutinized.

Learn how the brain creates memory pathways then utilize the process.

You must discover what you do not know.

Homework is meant to reinforce knowledge, so value it!

Planning is vital. Use a calendar to plan your responsibilities, then stay committed to the plan.

Stop multitasking while studying!

Write down important information and keep it organized for quick reference, then refer to it continuously.

Study with a conceptual approach. How does what I am studying relate to the functionality of real “live” events?